What is

“colonial” in the archives of the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision?

PART 3: The “postcolonial” period (after 1975)

Emily Hansell Clark

Part 1: The colonial period (1949–1975)

Part 2: The “decolonial” period (1949–1975)

Part 4: The contemporary

The “postcolonial” period (or, the continuation

of colonial relations): after 1975

Towards the end of the twentieth century, broadcast media in the Netherlands and internationally proliferated, with many more production companies, channels, and amateur access—which makes the NISV archive for this period harder to trace through item-level analysis, but potentially more fruitful to trace in terms of keywords and quantifiable trends. Here I focus on broad events and trends, some identified by other scholars, that provide evidence of the “afterlives” of colonialism in history and in the media archive.

In the period after 1975, the Antilles remained a part of the Dutch kingdom (through the present) while Suriname gained its independence from the Netherlands. In Suriname, through a series of volatile events including a military coup and political assassinations, migration to the Netherlands continued and established Surinamers as one of the most significant Dutch migrant groups. Media intended specifically for Surinamers and other migrants in the Netherlands found a place, such as the radio show “Zorg en Hoop” (1977 –2008). Likewise, groups of “guest workers” became established as permanent populations of the Netherlands, with workers from Turkey and Morocco becoming particularly visible due to their larger numbers and to curiosity and fears about Islam. Meuzelaar (2014) investigates particular images and tropes that recur during these decades in reports about Turkish and Moroccan immigrants, focusing on coverage of “exotic” rituals such as those that accompany Ramadan. News reports from this period covered guest worker protests and anti-immigrant violence; the government also launched series of informative broadcasts to encourage Dutch people to accept, or at least tolerate, the presence of foreign workers. Shows such as “Medelanders Nederlanders” (1980s –1990s) were also produced “about and for allochtonen in the Netherlands” (another problematic term that appears in the archive, both as a term of classification and a subject of more recent debate).

The Netherlands’ relationship with Indonesia and with its own colonial past in the East Indies is another theme to trace during this “post-colonial” period. As scholars have identified, this long history involving generations of colonial expatriate families stationed in the Indies is sometimes viewed with a particular nostalgia, by both white Dutch and Euro-Indonesians in the Netherlands. An example of this in media is the “Late Late Lien Show” of the 1970s–1980s, a comedy show that features nostalgia and longing for the “good old days” in the Indies. The episodes are hosted by Aunt Lien, an “Indo” auntie played by a white Dutch actress affecting an Indo accent, and feature sketches, songs, Indonesian music and dance, and stories about “Old Indië.”

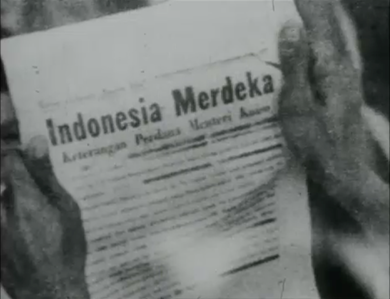

Even while this colonial nostalgia persisted, Dutch media and society began to reconsider the events of 1945-49 in Indonesia with a more critical eye. This began notably with the appearance of J. Hueting, a veteran of the Indonesian war, on the news show “Achter het Nieuws” in 1969. He gave an eyewitness account in which he called the events of the late 1940s war crimes—rather than “Police Actions” to keep the peace, as they were long referred to in Dutch. In the 1970s and 80s, archival footage was sometimes reused in these reexaminations, such as in Indonesia Merdeka (1976), a three-hour documentary by Roelof Kiers. The footage, which mostly came from Multifilm Batavia and thus was originally created to emphasize peace and order, often had to be creatively appropriated, such as zooming into the face of an Indonesian to show a look of fear. Hendriks (2015) argues that even with re-editing, it is still hard to use this footage to demonstrate to a contemporary audience that this was a colonial war of atrocity and violence (12). Another tact is to combine archival footage with eyewitness accounts; or to focus on interviews with Indonesian survivors, which was the approach of ‘De Excessen van Rawagedeh’ (1995). At the same time, there continues to be media that deals with the war in Indonesia in a non-critical manner, such as an episode of “Trugkike: Bataljon Zeeland 3” which sets old military footage to 1940s jazz music, celebrating the veterans who took on and managed the “enemy” Indonesians1.

Next: Part 4: The contemporary

Notes

1 Knowing what we now know about the Indonesia’s War of Independence, observing such willful ignorance of the past in recent media is quite disturbing.References

- Berkhofer, R. F. (1995). Beyond the great story: History as text and discourse. Harvard University Press.

- Jansen Hendriks, G. (2015). “Goodwill ambassador”: The legacy of Dutch colonial films. VIEW Journal of European Television History and Culture, 4(8), 21. https://doi.org/10.18146/2213-0969.2015.jethc090

- Jansen Hendriks, Gerda, G. (2020). Nascent or drowsy? Dutch newsreels made in Indonesia between 1947–1950. Critical Archival Engagements with Sounds and Films of Coloniality, 55–59.

- Kuitenbrouwer, V. (2020). The semantics of decolonisation. The public debate on the New Guinea Question in the Netherlands, 1950–62. In B. Sèbe & M. G. Stanard (Eds.), Decolonising Europe? Popular responses to the end of empire. Routledge.

- Kuitenbrouwer, V. (2016). Radio as a tool of empire. Intercontinental broadcasting from the Netherlands to the Dutch East Indies in the 1920s and 1930s. Itinerario, 40(1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0165115316000061

- Meuzelaar, A. (2014). Seeing through the archival prism: A history of the representation of Muslims on Dutch television [PhD thesis]. Universiteit van Amsterdam.

- Jansen Hendriks, Gerda, G. (2020). Verloren Banden: Moluccan footgage, articulating perspectives in postocolonial Netherlands. Critical Archival Engagements with Sounds and Films of Coloniality, 60–63.

- Stoler, A. L. (2002). Colonial archives and the arts of governance. Archival Science, 2(1–2), 87–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435632

- Stoler, A. L. (2009). Along the archival grain: Epistemic anxieties and colonial common sense. Princeton University Press.

- Zeitlyn, D. (2012). Anthropology in and of the Archives: Possible Futures and Contingent Pasts. Archives as Anthropological Surrogates. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41(1), 461–480. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145721