What is

“colonial” in the archives of the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision?

PART 2: The “decolonial” period (

1949–1975

)

Emily Hansell Clark

Part 1: The colonial period (1949–1975)

Part 3: The “postcolonial” period (after 1975)

Part 4: The contemporary

The “decolonial” period (or, from Indonesian independence to Surinamese independence): 1949–1975

Between the Dutch formal recognition of Indonesia’s independence in 1949 and Suriname’s independence in 1975, the Kingdom of the Netherlands went through a process of reorganization, with a renewed focus on its territories in the West Indies. In this section I focus on materials in the NISV archive related to Suriname and the Antilles, then discuss other more ambiguously colonial events of this period, involving control of West Papua and migrations of people from the Moluccan Islands as well as Turkey and Morocco to the Netherlands .

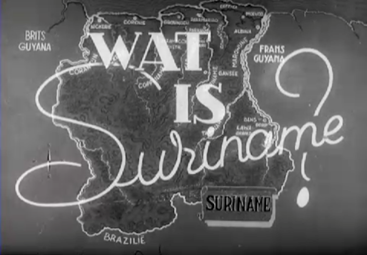

The NISV archive shows in its contents that as the Netherlands began to come to terms with its loss of Indonesia as a colonially subjugated territory, government and public interest in the West Indies—Suriname and the Antilles—began to rise. For example, I survey here news media coverage of Suriname, which essentially begins in 1941 with some attention to the US troops stationed there during World War II to defend bauxite mines essential to the aluminum supply. A pro-Netherlands propaganda film produced by the Netherlands Information Bureau for an American audience in 1943 mentions the Dutch “stewardship rather than ownership” of colonial wealth in the Caribbean. In 1947 –48, Polygoon Profilti produced a series of short films, ‘Films About the West,’ introducing each of the Caribbean colonies to the Dutch cinema audience (one of these films is called “What is Suriname?”). Polygoon weekly news journals in the late 1940s include items labeled “News from the West” which show Suriname’s citrus and coconut industries (including shipping these to the Netherlands) and its bauxite mines. Such news items appear with steadily increasing frequency.

In the 1950s, three visits by members of the royal family to Suriname and the Antilles instigate an explosion of news coverage: Prince Bernhard in 1950, Queen Juliana and Prince Bernhard in 1955, and Princess Beatrix in 1958. These trips brought teams of cameramen and attracted amateur videographers as well. The NISV contains video footage of the royals’ tours of various islands and of the capital and interior of Suriname, where they were ceremoniously greeted with traditional music and dance by representatives from each of Suriname’s ethnic populations. The footage is used and reused in various reports and news clips.

In the 1950s and 60s, filmmakers also traveled to the Caribbean to make longer documentary films, often with an anthropological bent, about West Indies nature and culture. Notable films made by Dutch visitors include Herman van der Horst ’s Faja Lobbi (Suriname, 1960) and John Fernhout ’s Blue Peter (Antilles, 1957) and ABC (Antilles, 1958)1. The filmmaker Peter Creutzberg was based in Suriname for much longer, from the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s. In addition to providing footage to Dutch news, he created a number of films about the West Indies colonies, including Corsow (Antilles, 1966), De Gouden Zwamp (Suriname, 1971), and Wageningen (Suriname, 1971). In addition, Creutzberg founded the Filmgroep Suriname to train local filmmakers, which produced short films about health work and industry in Suriname that were edited in the Netherlands and shown to Dutch audiences. These films were often focused on Suriname’s development and modernization.

One issue for these materials in the NISV archive is the changing and outdated terminology that is often used for different ethnic groups in the Dutch West Indies. Terms such as “bosn*ger” for different groups of Maroons and “indianen” for Indigenous groups are no longer used, but appear not only within these films but in their metadata as well. While shots of Suriname’s nature and culture often appear with an anthropological distance, sometimes un-narrated and un-soundtracked (for example in Van der Horst’s Faja Lobbi), these films are typically made by Dutch filmmakers for a Dutch audience and conform to particular expectations about abundant, overwhelming nature and exotic cultures: persistent colonial tropes about the Caribbean.

Finally, in the 1970s, slowly brewing political changes and tensions resulted in Suriname’s official independence from the Netherlands in 1975. A relatively huge amount of news footage shows celebrations in Paramaribo as well as in the Netherlands. Meanwhile, the actual events surrounding Suriname's independence involved not only celebration, but political instabilities and fear for the future, especially for those not aligned with the new ruling party. This resulted in a mass migration of many Surinamers to the Netherlands in the 1970s and 1980s, which I discuss in the next section. The representation of Surinamese independence in Dutch news—the proceeding discussions, joyful celebrations, and ensuing waves of migration—is a topic yet to be studied and analyzed in the NISV archive.

I have focused on coverage of the Dutch colonies Suriname and the Antilles during this period after Indonesia’s independence, but a number of other events also fall under the purview of colonial relations. First, the Netherlands’ conflict with Indonesia over the future of West New Guinea (West Papua) in the 1950s –60s. Kuitenbrouwer (2020) explores the Dutch debates over this through newspapers, searching terms such as “Papua” “self-determination,” and “decolonization”; it would be interesting to see if the audiovisual coverage in NISV’s collections support his findings, namely that the term “decolonization” was first widely used in Dutch news in the context of this conflict. Further, Kuitenbrouwer finds that the Dutch often make a problematic racial distinction between Indonesians and Papuans that is used to argue for the latter’s continued subjugation2. These mid-twentieth-century debates about West Papua fit into a complex colonial history (including the division of the island of Papua and its colonization by Spanish, German, British, and Dutch powers) and into contemporary debates about West Papua's ongoing colonization by Indonesia (see the Free West Papua movement, including in the Netherlands). Further, the notion of race in context of Papua is also up for debate: at present, many Papuans refer to themselves not as Asian but as Melanesian, a term derived from the word "melanin" and referring to the darkness of Papuans' skin.

Again related to Indonesian independence and decolonisation, people from the Moluccan Islands arrive in the Netherlands starting in the early 1950s. Mostly Muslim, Moluccan migrants in the Netherlands are housed in barracks, establish some of the first mosques in the country, and become the target of discrimination and growing conflicts with the Dutch government and Dutch publics. This peaks in the 1970s, with a number of widely publicized incidents carried out by people portrayed in Dutch news as radical terrorists. Pattikawa (2020) explores this theme in the NISV archive, and there is more work to be done towards a systematic analysis of how Moluccans are portrayed in Dutch media over this time period.

The arrival of “guest workers” from foreign countries inside and outside of Europe in the Netherlands becomes a topic of societal debate in the late 1950s and 1960s. The term “gastarbeider” (guest worker) first appears in the NISV archive in news reports from 1957. Early appearances of this term are in reference to Southern European labor migrants, and include a radio program for Spanish-speaking guest workers, as well as news reports about Italian guest workers being called “nasty spaghetti eaters” and told to go home. Meuzelaar’s (2014) extensive work on the (often stereotypical and problematic) representation of Muslims in Dutch TV in the NISV archive begins with the arrival of guest workers from Turkey and Morocco in the early 1960s. Meuzelaar describes in particular one episode of the news program ‘Televizier’ from 1969 about the recruitment of Moroccan guest workers, which becomes a recurring image reused over the years in other broadcast media to symbolize an influx of Muslim workers. The arrival of Otherness—especially Islamic Otherness—in the Netherlands during this period sets the stage for a rapidly expanding Dutch “multiculturalism” as well as the xenophobia and Islamophobia that developed with it, which I discuss further in the next parts.

Next: Part 3: The “postcolonial” period (after 1975)

Notes

1 Fernhout worked for the Netherlands Information Bureau in New York, created an earlier controversial film about the Indonesian War of Independence, Indonesia Calling, and also traveled to Suriname to provide news footage of Queen Juliana’s visit.2 Another problematic term that seems to arise frequently in coverage about New Guinea: “snellenkoppers” or “headhunters.”

References

- Berkhofer, R. F. (1995). Beyond the great story: History as text and discourse. Harvard University Press.

- Jansen Hendriks, G. (2015). “Goodwill ambassador”: The legacy of Dutch colonial films. VIEW Journal of European Television History and Culture, 4(8), 21. https://doi.org/10.18146/2213-0969.2015.jethc090

- Jansen Hendriks, Gerda, G. (2020). Nascent or drowsy? Dutch newsreels made in Indonesia between 1947–1950. Critical Archival Engagements with Sounds and Films of Coloniality, 55–59.

- Kuitenbrouwer, V. (2020). The semantics of decolonisation. The public debate on the New Guinea Question in the Netherlands, 1950–62. In B. Sèbe & M. G. Stanard (Eds.), Decolonising Europe? Popular responses to the end of empire. Routledge.

- Kuitenbrouwer, V. (2016). Radio as a tool of empire. Intercontinental broadcasting from the Netherlands to the Dutch East Indies in the 1920s and 1930s. Itinerario, 40(1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0165115316000061

- Meuzelaar, A. (2014). Seeing through the archival prism: A history of the representation of Muslims on Dutch television [PhD thesis]. Universiteit van Amsterdam.

- Jansen Hendriks, Gerda, G. (2020). Verloren Banden: Moluccan footgage, articulating perspectives in postocolonial Netherlands. Critical Archival Engagements with Sounds and Films of Coloniality, 60–63.

- Stoler, A. L. (2002). Colonial archives and the arts of governance. Archival Science, 2(1–2), 87–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435632

- Stoler, A. L. (2009). Along the archival grain: Epistemic anxieties and colonial common sense. Princeton University Press.

- Zeitlyn, D. (2012). Anthropology in and of the Archives: Possible Futures and Contingent Pasts. Archives as Anthropological Surrogates. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41(1), 461–480. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145721